A similar study was conducted specifically for investing/market forecasts. The CXO Advisory group gathered 6,582 predictions from 68 different investing gurus made between 1998 and 2012, and tracked the results of those predictions. There were some very well-known names in the sample, but the average guru accuracy was just 47%--worse than a coin toss. Of the 68 gurus, 42 had accuracy scores below 50%.

Another study of analyst estimates conducted by David Dreman showed that across 400,000 different estimates, the average error was 43%! (It is interesting to note that Dreman was was of the "gurus" from the CXO study--but he was the 5th best overall with an accuracy of 64%).

Back to Tetlock’s study, which uncovered one variable that did effect whether the expert was more or less accurate:

It made virtually no difference whether participants had doctorates, whether they were economists, political scientists, journalists, or historians, whether they had policy experience or access to classified information, or whether they had logged many or few years of experience in their chosen line of work. The only consistent predictor was, ironically, fame, as indexed by a Google count: better-known forecasters—those more likely to be fêted by the media—were less well calibrated than their lower-profile colleagues.

The problem isn’t that these experts are dumb—indeed, they are usually very smart. The problem is that it is nearly impossible to predict outcomes in complex, adaptive systems like the stock market or the economy. J.P. Morgan (the original) had the only appropriate and accurate market forecast: “it will fluctuate.”

A Forecast Free Investing Process

Instead of basing your investment decisions on subjective forecasts, base them on simple rules or models. Many people don’t like models because they are impersonal and “backward looking.” We want insight and prediction; models just spit out an answer. Of course models aren’t perfect, but they can be really helpful.

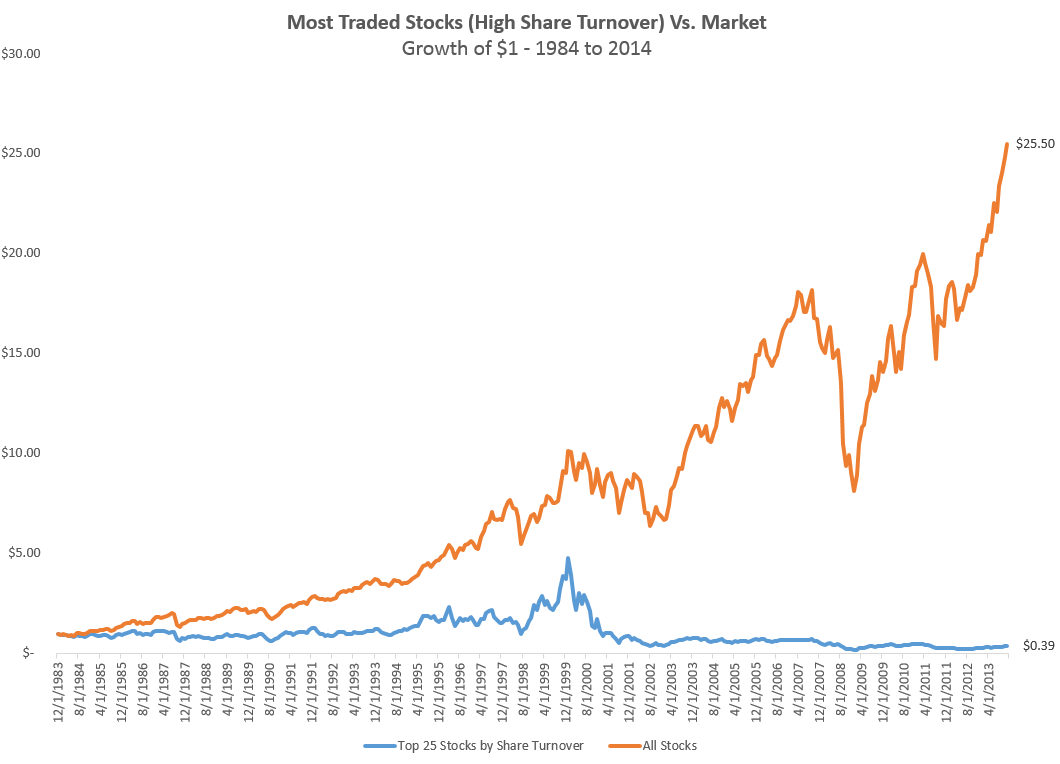

Simple models almost always beat experts. They are consistent, data driven, and easy to apply. From wine prices (Orley Ashenfelter), to political elections (Nate Silver) to individual stock returns—models work; and they use information that is already available instead of relying on forecasts about the future.

Ben Graham was the father of investing models—his checklists for the defensive and enterprising investor were decades ahead of their time. Similar systematic approaches are gaining popularity in the form of smart/strategic beta. These tend to be watered down applications of great ideas like value, momentum, or quality, but they can be a good start. The key with a modeling approach is to be consistent and stick with it. It is always most tempting to abandon a model when it’s suffering through an inevitable period of underperformance—but that is the worst time to leave (think of a value strategy in 1999).

Quants are the heaviest model users, but the important point here is that you should have rules and a consistent process. Many of the most famous investors aren’t quants, but they often have a system: a set of rules consistently applied when buying and selling. Here are a few examples of model or rules based projections that have worked quite well for the market.

One frequent criticism of models is that using them is like driving by looking in the rear-view mirror. They only look backwards—at what has already happened—and never look forward to what will happen. But anyone making this objection is planting the axiom that others can successfully look out the windshield and accurately see what is coming. The evidence above suggests otherwise.

The CAPE ratio, for example, is very “backward looking,” because it uses data from the past 10-years. One of the most common criticisms of the CAPE ratio is that 10 year old data is irrelevant in today’s market environment (“it’s different this time!”) Yet as Meb Faber has shown, a simple strategy that buys markets with the lowest CAPE ratios does very well (read this). The beauty of the CAPE model is that if forces you into terrible situations where the forecasts for the future are dire. Low CAPE ratios result from very bad news, fear, and forecasters whose consensus is that the market is going to hell (think Greece, or Russia today).

We rely on stories and circumstances when we should care more about price. The story about each cheap market is always different, but the psychology that creates each attractive market opportunity is always the same. That is why investment models like CAPE work: they prey on the mistakes of fallible human investors and don’t get caught up in trying to figure out each new, market circumstance. A CAPE ratio tells you nothing about what will happen to any given country in the future, but it identifies markets that may have been mispriced.

Ignore Experts, Think For Yourself

Jiddu Krishnamurti, a great thinker and writer, spent his life urging others to investigate things for themselves rather than rely on experts. Two passages from his book Freedom from the Known urge us to step up our game: