There isn’t a more commonly recited investment strategy than “buy good businesses at good prices.” This simple strategy sums up much of Warren Buffett’s success, and countless investors have attempted to mimic his style. Indeed, when I asked those on twitter what their favorite investing ‘factor’ was, the most common response was price-to-book (P/B) divided by return on equity (ROE). The idea behind the simple ratio is to find good businesses (high ROE) at good prices (low P/B). This factor is similar to another similar two-factor comparison, Joel Greenblatt’s “magic formula,” which also combines a measure of good businesses (high return on invested capital) and good prices (cheap earnings-before-interest-and-taxes to enterprise value).

I rebuilt the factor since 1963, ranking all stocks by P/B-to-ROE and sorting them into deciles[i]. Since each decile represents several hundred stocks (and is therefore unrealistic for individual investors to manage) I’ve also included a concentrated, 25 stock strategy which selects the best stocks in the market by this measure. So does this simple measure help you find stocks that will outperform the market? The answer is a qualified yes. The top 20% of the market by the P/B-to-ROE measure does tend to outperform by a decent margin…but the concentrated portfolio isn’t as impressive.

Results

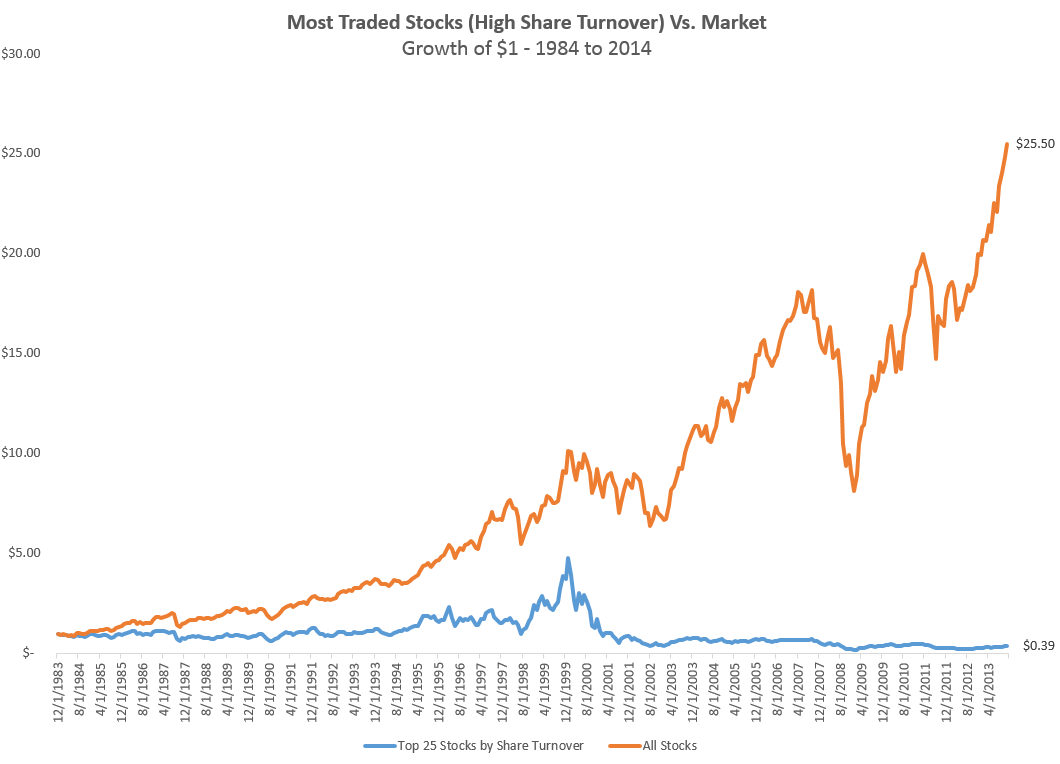

Here are the results for the 10 deciles—and the 25-stock strategy—versus the market. Both of the top two deciles outperform the market, but the second decile provides the highest Sharpe ratio.

More curious is that the concentrated version doesn’t do all that well. While it does beat the market over the very long term, it is not at all consistent. In rolling 10-year periods, it only beats the all stock universe 26% of the time—before costs. If transaction costs and taxes were factored in, it wouldn't be worth it. As for the top decile, you'd have to be very patient to win with this strategy. There has been a 1-in-5 chance, historically, that the best decile underperforms the market in a 5-year period--and again, that is before costs.

I should note that price-to-book is the least impressive value factor I’ve tested, and ROE is the least impressive measure of quality/profitability. EBITDA/EV, for example, yields much better results than P/B, and ROIC yields much better results than ROE. Is this just historical coincidence, a small bit of data mining? It is impossible to say, but there are compelling reasons for using factors other than P/B and ROE—but that’s a topic for another post.

Let me know if you have other ideas for testing, email me at Patrick.w.oshaughnessy@gmail.com

[i] Deciles are rebalanced on a rolling annual basis, and companies with negative earning and/or negative equity are excluded.